Navigating Disorder: Managing Disarray Without the Insistence on Command (Akomolafe)

Podcast* Season 1,* Episode 7

Getting Lost in the Middle: A Conversation on the Third Way with Bayo Akomolafe

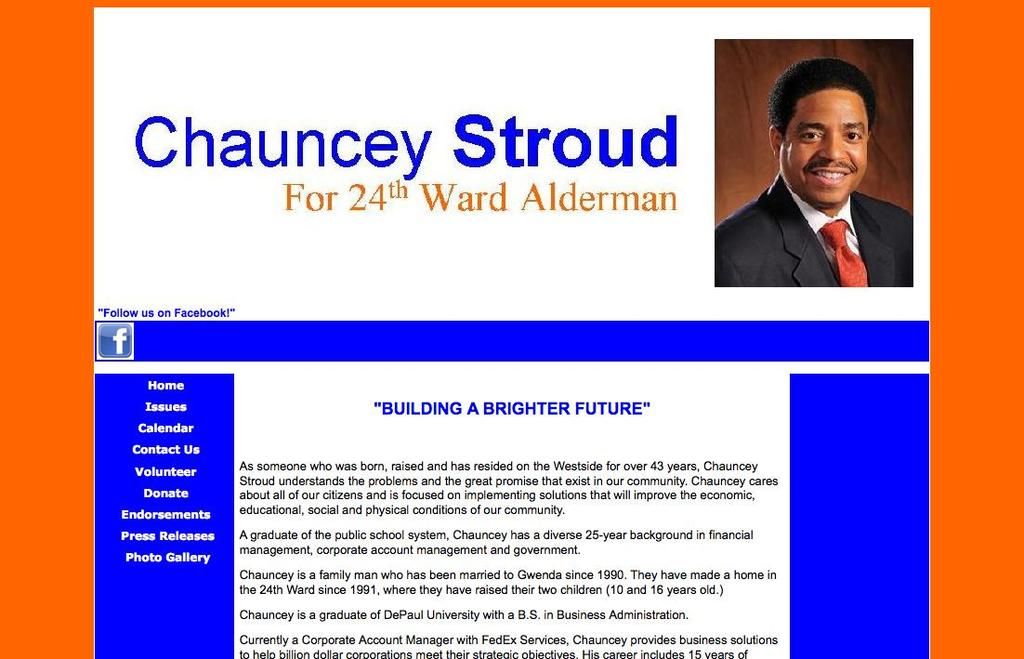

Photograph by Arianna Lago

Podcast* Season 1,* Episode 7

In the latest episode of The Nature Of podcast, philosopher, poet, and thinker Bayo Akomolafe joins Willow Defebaugh for a mind-bending conversation on transcending binaries and embracing the liminal spaces of emergence.

To not miss an episode of The Nature Of, be sure to follow here.

What if the rupture of these tumultuous times is not an ending, but an opening? In this episode, Willow speaks with Bayo Akomolafe, a revolutionary philosopher, poet, and thinker whose work challenges us to step beyond binaries and into the fertile, unpredictable space of emergence. They dive deep into the murky waters of transformation, exploring how the path to renewal doesn't lie in rigid certainty or oppositional thought, but in the cracks where new possibilities take root. Nature doesn't solve tension; it composts it, making way for something unexpected to bloom. Bayo invites us to see the chaos of our moment not as a catastrophe to be avoided, but as an invitation to let go of our old ways of being and embrace the "third way"-the space between and beyond, where new ways of relating, knowing, and becoming can unfold.

About the Guest

Bayo Akomolafe (Ph.D.), rooted with the Yoruba people in a more-than-human world, is the proud papa to Alethea Aanya and Kyah Jayden Abayomi, the grateful life-partner to Ije, son, and brother. A widely celebrated international speaker, posthumanist thinker, poet, teacher, public intellectual, essayist, and author of two books, These Wilds Beyond our Fences: Letters to My Daughter on Humanity's Search for Home (North Atlantic Books) and We Will Tell our Own Story: The Lions of Africa Speak.

Bayo Akomolafe is the Founder of The Emergence Network, a planet-wide initiative that seeks to convene communities in new ways in response to the critical, civilizational challenges we face as a species. He is host of the postactivist course/festival/event, 'We Will Dance with Mountains'. He lectures at Pacifica Graduate Institute, California, and sits on the board of many organizations, including Science and Non-Duality (in the US) and Ancient Futures (in Australia).

Episode Transcript

NARRATION

When gazing at the state of the world these days, it can feel like everything is spiraling out of control. We're living in a maelstrom of chaos and polarization, and it's impossible not to feel overwhelmed. But what if this storm isn't the end of the story, but the beginning? What if it's from within the whirlwind that something new is trying to emerge? That's why I was so excited to talk with Bayo Akomolafe for this week's episode-because in those swirling vortexes where his work thrives, he investigates the promise and possibility that a maelstrom holds. My name is Willow Defebaugh, and this is The Nature Of. Each week, we'll look to the natural world for insights into how to navigate the experience of being human.

This week, we're exploring the nature of emergence.

Emergence is the phenomenon of complex natural systems arising organically. For example, a forest isn't born out of a specific plan. It emerges from seeds sprouting in fertile soil, responding to conditions around them. From there, plants and trees grow, attracting pollinators and animals that disperse nutrients, fungi forming networks below the ground. Before you know it, an entirely new world is born. Bayo invites us to see ourselves as part of that intricate web of emergence. He's one of the most brilliant minds I know, and every time we speak, I'm left with a fresh perspective. So, you can expect our conversation to get a little philosophical, but stick with us because I promise what you'll get from it is worth it.

Willow Defebaugh

Bayo, one of my favorite things about speaking with you is that you are such a gifted storyteller in addition to the wisdom that you hold. So I'm wondering as we kick off this conversation about emergence, do you have a story for us to help illustrate this concept?

Bayo Akomolafe

There are several examples that jump to mind, each salacious. Let me cite a simple example, one that is dear to me that I've been traveling. Someone gave me a puzzle piece set. It had pieces shaped like the Tetris game, and of course, the aim of every puzzle was to piece things together in the ways that the manufacturer has predetermined that they should be pieced together. My son took the puzzle piece and started to dismantle it. He doesn't usually say thank you. He's autistic, I should say. He has no time for all those neurotypical conventions. He took it from me and went down to business. I left him for a bit. I came back, and he had his hand outstretched and he had in his small fist a few despondent pieces of that puzzle. And he said, "Dada, could you throw this away for me?" Which worried me. I was like, "That's not exactly how puzzles work. The aim, my dear son, is to put all the pieces back together again."

I tried to explain that to him. He wasn't budging. He insisted, and so I took it and pretended like I was throwing it away, but I put them in my pocket. Went on to do my business, came back and he had other grieving pieces of the puzzle, and I tried again to explain, but I noticed that he wasn't going to budge. And then I moved closer to what he was doing and noticed, to my great surprise, that he was arranging the pieces according to their similarity-not according to how they fit to some manufacturer's predetermined model. So the sevens-each in blue, yellow, green-the sevens were arranged in a linear progression. The other pieces were arranged in another progression. And, of course, when you do the puzzle that way, it takes up more space than it needs to.

But then in that moment, I realized that there were two autisms at work. One was my son's autism and the other was my oughtism, except that I spelled mine O-U-G-H-T-I-S-M, that it ought to be this way, that it ought to work out this way. I was invested in the manufacturer's vision for how the puzzle should work, and my son was playing with the world differently and disrupting and dissing the purpose of things. And maybe that's my story. That, and I have 100 of them, of how other kinds of agencies spill through the purpose or the functionality or the instrumentality or the utility of a thing.

Willow

I really cherish every time you share a story about your family because I learn so much. The puzzle story brings up for me strategy. We live in this world that is so dominated by strategy. We have to think our way out of every puzzle, every problem. And emergence offers this other invitation, which is, "How might things perhaps naturally want to coalesce or converge?" I mean, slowing down, moving at the pace of the world, is something that we've spoken about a few times, and it's so clear how, in a way, strategy is in opposition to that because strategy is trying to get ahead of the world. It's trying to always be in the future, never here, never present to what is emerging. I wanted to ask you, in a world that feels like there is so much urgency, where there are all of these compounding crises, what emerges when we actually allow ourselves to slow down?

Bayo

So, this is something that I should confess, Willow, but don't share it with anyone, okay? This is just between you and I. I love cartoons and I love beautiful animation. I do a lot of good thinking with that filmic exploration. There's something animation can do that live-action can't do. So, I love animation. There's one I started to watch recently called Common Side Effects. It's on HBO Max. It's amazing. It's beautiful. I will spoil it because I'm Nigerian. Just a brief spoiling here. It is about a mushroom called the Blue Angel mushroom that heals everything. Just a little shake of its dust in the mouth of a beheaded pigeon can actually reanimate, can reanimate dead objects or sick people or people suffering from dementia. Except the pharmaceutical industrial complex does not want this to come out because they're invested in keeping people well, you see? And this wellness that this Blue Angel mushroom offers is a disruptive kind of wellness, which cannot be monetized, at least at the moment.

In episode three-That's how into it I am. In episode three, the protagonist, he's trying to grow these mushrooms because he's run out of his supply and he's trying to raise these mushrooms in his backyard. He of course, salvaged the few that he found near a giant pharmaceutical factory, which was the runoff that was spillage was toxifying and poisoning the entire environment. And so he salvaged the pieces he found and he was trying to raise these pieces or new pieces of this mushroom in a pure environment. I'll skip to the chase where he realizes that it's not that the mushrooms were growing in spite of the spillage, it's that they were feeding on the spillage, on the poison, and it changes everything.

I remember just immediately grabbing my journal and writing in it, "weird fidelities." By weird fidelities, modernity really teaches us to think in terms of binaries. Left, right. Good, bad. Fidelity, infidelity, stuff like that. I wonder about the tensions between where the very enactment of purity creates the conditions for contaminants to thrive. That sometimes, in sterile environments in utopia, the very conditions for dystopia might emerge. It could be a mushroom sprouting in Chernobyl, it could be the devil sprouting in the Garden of Eden. The world is more complicated than those binaries that we're habituated to, and that it might very well be in turning away from things that we face them squarely. That's the idea of weird fidelities, but it also feeds the other concept of post-activism. And what I call post-activism is noticing how the ways we respond to the crisis is part of the crisis.

So, imagine well-intentioned activists in this animation, in this cartoon doing their darnedest to tear down that wall, Gorbachev-style, to tear down that pharmaceutical complex. To say, "We don't want this spillage any longer." It would be acting at odds with the very thing that could actually release them from entrapment, from incarceration within that complex. So maybe that's my idea here. There's a way that white modernity works where it can actually enlist the adversary, the counter-cultural project, the protester. It can enlist the infrapolitics into its workings, so that the virus and the antivirus maintain the same thing. And I'm invested in a third way, this weird fidelity issue, climbing aboard the slave ship and sailing into the womb of the transatlantic slave trade. Not seeking victory, not eschewing defeat, but noticing that something about transversely crossing the Atlantic in a way that does not guarantee solutions opens up new spaces of power. I realize I may have traipsed far off the question that you asked.

Willow

Well, you traipsed off into at least three other questions I wanted to ask you, which we will all get to. But the one I'll start with is the third way, because this framework-this non-binary thinking-could not be more relevant for the world that we're living in today where it feels like binaries are everywhere and polarity is at an extreme. And it's interesting that you bring up the case of-well, first of all, I'm very excited to watch the show. We've done stories on a few different ecotopias and the kind of shadow sides emerging within them, within utopia. And I always think about that. What is it about trying to develop a place that's rooted in good or perfection or whatever else, that inevitably brings about the seeds of its opposite that is part of what created it in the first place? I'm very interested in that train of thought. But where it leads me is, how do we practice rising above the binary? How do we practice the third way in our everyday lives, stepping outside of the binary, especially in these times of extreme polarity?

Bayo

I'll offer something that will shock us away from the economy of that question. I don't think that we can. I don't think it's left to us. I don't think it's a skill to develop. I think to live, to exist, is to be defeated over and over again. That is, we are the frothing edge of an explosion that is still happening that we rudely call reality or space-time or whatever you want to call it, or God. This panentheistic procession of orgasmic possibilities that is branching out diffractively in a way that we'll never be able to control.

What Bayo is pointing toward here-that frothing edge of an explosion that's still happening as he so poetically put it-is the Big Bang. "One might call the Big Bang the original rupture." Ever since it occurred, life has been experimenting and iterating, failing and adapting, leading to life as we know it. So, what he's pointing toward here is an invitation to think differently; to embrace the understanding that life itself has failed many times across evolution, producing new species and new forms of life and ways of being. That's what Bayo means when he says, "to exist is to be defeated over and over again." That's a sentiment we know all too well with environmentalism and other social movements.

Willow

I want to come back to what you shared around post-activism. So, I think how we respond to crisis is part of the crisis. We are entangled with that which we resist. We are what we resist. And I'm curious if you can speak to how do we hold post-activism, and how do we engage with injustice at the same time in a way that honors identity or complexity, but also doesn't fall into-I guess-the traps of activist ideas of the past?

Bayo

Well, you see what's happening in the United States today-upon Trump's second assumption of power-there seems to have been this dramatic culture shift. Even Mark Zuckerberg gave this tech-bro speech where he says, "It seems culture is shifting." And all of a sudden, everything that progressives have worked hard to install as part of mainstream culture is fading away, is losing its value. DEI, LGBTQ, who cares? Philanthropic organizations are now stripping themselves and their websites of these things. They're purging. And so it seems like this about-face, this shocking thing has happened, and I wonder about that.

What I particularly wonder about is how morality works. And by morality, I don't mean a stable structure. I mean something dynamic, rendered visible by legislation or laws or unspoken rules about behavior, or stuff like that, but how morality as an ontological, epistemological force shapes what is possible. And how logics are maintained even in the face of damning, dramatic, cultural shifts like the United States is experiencing right now. It seems like it's the pendulum, it's swishing or moving from left to right, left to right. And you might say, "Oh, this is dramatic." But no, the pendulum, as this dome-like structure or relational, processional, dynamic structure that is moving and responsive maintains a logic. It maintains bodies in a particular way. In the same way, Sister, I wonder about justice, too. And how the very enactment of justice, the ethnography of justice maintains injustice. That something about how justice works makes injustice possible.

So, I speak about post-activism as a kind of opening, as an eruptive moment, as a crack that disrupts the ongoing continuity of this vocation of, "Oh, we're going to pull down that power. Oh, now it's the left's turn to be outraged. Oh, it's the right's turn to be outraged," and blasting out of the entire game without transcending the game, but blasting out of it and noticing that this is indeed a game. The pendulum is moving from left to right, and we're constantly trying to pull it to our side, but the logic is maintained.

Are there other ways of framing and embodying lives and futures that does not cohere with this game that we're entrapped in? That is the vocation of what I call parapolitics, which is a cultivation of different modes of perception that might allow us to visit and be visited by the world that we are trying to resolve. The third way is not a third thing in the numerological or numerical sense, but it's a transversal cutting open of the failure of a binary. It's when binaries fail to produce novel things, new kinds of things. And when that happens, I feel that new space of politics has opened up. It's a different question than what that politics consists of.

Willow

Beautifully put. We can't really talk about emergence without talking about the unknown and the mystery because that is a massive part of it. And at the risk of creating another binary, I think with the rise of authoritarianism here and in other places, which is so much about control from a select few amount of people, emergence-which is a surrendering of control and honoring the complexity, vast complexity-there's something in that to me that feels like the answer, and it is not really about arriving at a solution. It is perhaps being more curious about the spaces and the cracks. And that is perhaps the moment that we are living into right now. And every day I hear people asking me, "Well, what do we do? What do we do?" I was just speaking to someone the other day about this, and I shared that when I feel like there isn't an obvious to-do, it's perhaps because there is nothing to do yet, and perhaps that's the pregnant pause that we're in, in a lot of ways in these current politics.

Bayo

Isn't that humbling, Willow? There's nothing to do yet. It runs against everything we've told ourselves, that there's always something to do. Think about the ways we think about that glorious binary, that other binary that is present even now in our conversation. Apathy, agency. It's either you're part of the problem, or you're part of the solution. It's either you're doing something, or you're hurting those who are doing something. It's such a strict, brittle, and rigid binary that it does not notice. It doesn't know how to notice the tiny inflections, the spillages and leakages, the ways that purity hurts itself, the way that purity is already impure.

It doesn't know how to notice those things that mean that the world isn't straight and narrow. The American state started out as a promise: the promise that we can co-enact a regime of governance that is safe enough to try, in which the promise is not getting things done. The promise is, "What is safe?" What is safe enough that honors every single person as an active agent in determining the shape of our government? What is safe enough to try?

I've noticed the new spiel on CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News. The new argument seems to rotate around, "Well, Trump is getting things done. He's getting things done. Why are you complaining? Why are you liberals complaining? Trump and his boss, Elon Musk, are getting things done. They're getting things done." And I wonder to myself, when was it about getting things done? Because if it was simply about getting things done, then we should just have a monarchy. Which tells me again, Sister, that the logic of monarchy has always been part of the democratic arrangement.

It never really left. Just like the slave ship never really disappeared, it just regurgitated its guts and became the shore, and its hierarchical arrangement of bodies, privileged bodies over Black bodies, over natural resources became transferred into or reinforced the shore. The hinterlands, the borderlands. In the same way, America never really got rid of its monarchical origins. Even though it fought against the British Empire, it maintained the logic. Now, those tensions with new technologies, new arrangements, those tensions that were hitherto hidden are simmering to the surface.

Willow

I wanted to go back to what you shared around, "When did the goal become getting things done?" Because I mean, you just summarized America in a question. But it occurs to me, we're having this conversation pretty much exactly five years after the COVID-19 pandemic started, and what that instigated in the world was a disruption in getting things done. And we saw so much bubble to the surface during that time. Amidst the grief and, of course, the loss, there was also so much revelation, I think. And to me, that was so tied to doing nothing. The "there is nothing to do" feeling that everyone was confronted with. And so, I think there is something to that from five years ago to think about in this particular moment when, perhaps, we are not bound by physical containers of isolation, but there is still perhaps nothing to do yet.

Bayo

I agree. There might be nothing to do, and yet everything to do. It might be the case that it's not ours to do. But I want to dwell on this idea that maybe the pandemic is also a part and parcel of the political moments that the United States, specifically, is experiencing right now. This idea of a seed crystal, that there are fundamentally, I guess, two ways that a crystal might form over eons of years in a cave somewhere or in a lab where a supersaturated solution could be inseminated with a seed crystal. And upon doing this, you can immediately grow a crystal in a lab. A seed crystal is inserted and freezes the supersaturated solution, and a crystal emerges faster than it would take when it does it naturally in a cave somewhere, I suppose. What seed crystals do is to crystallize tensions that are already within a solution.

What I said earlier about a democracy behaving or having those hidden tensions within it of behaving like a monarchy seem very true here, especially when you bring in a pandemic. Maybe the pandemic was the seed crystal that immediately turned politics on its head or allowed for those hidden tensions to become more solid. And so, the tension now became getting things done, even if it denies us the very slow-paced, unsexy, procedural, bureaucratic arguments and conversations that have hitherto seemingly characterized American politics. Now, it's who can punch faster; who can hit harder? And that is how the moral punctuates the ethical, how disruption can shape fields of thought and behavior.

Willow

I love the analogy of politics has become who can throw the hardest punch or who can throw the punch first. And, honestly, the reality is no one's questioning why they're in the boxing ring. No one's questioning the rules of the puzzle. And perhaps that's the best role that we can play. Just for my own curiosity, I want to pull the thread from the very beginning of this conversation, which was, "You mentioned technology and questioning do we really develop technology or is technology developing us?" Does it happen in tandem? How in your eyes does emergence relate to technology, particularly right now with the onset of AI and this moment that we're in?

Bayo

For a long time, we have been in rich, intergenerational conversations about agency, about the creator and the created, and how these minorized ways of thinking about roles in emergence obscure the complexity of emergence. How it is often the case that we are summoned by the created. I often give the example of microchimerism. It's almost Freudian in its dynamics. Biologists notice that cells do not just propagate from the mother holding a child in her womb to the child, but they propagate the other way, as well. The child taints, or stains, the mother with her own cells, and some fetal cells have been found in the brains of nursing mothers-which suggests to me what Freud was famous for saying: "The child has become the father of the man." The created creates the creator.

In the '70s, we were quite intrigued with how memory works. By we, I mean psychologists. I'm a recovering psychologist. But we were intrigued by how memory works, and we're seeking metaphors to understand memory. We have computer-laden language today because at this time, especially in the '70s, computer systems were becoming trendy and it was becoming more part of popular culture. The idea of the computer, hardware, software, garbage in, garbage out, processing, and all of that. And so, the language for forgetting-for memory-came from the study of computers. Now, think about that for a moment. We, in normal parlance, create computers which teach us how to think about cognition. The computer systems teach us how to think about our own selves so that in a sense, computers recreate us.

In the same way, AI is misnamed, it's a misnomer. There's something hubristic about the idea of thinking about the idea that these large language models are "artificial" and that we are the "natural intelligences" and they are just "artificial." What does it mean when we confront the very disturbing idea that human cognition might not be "human" after all, that we might have actually been sharing intelligence with technology and furniture and density and intensity and archetypes and ancestrality and spirituality and gastronomy and microbes all around us? What does it mean to stay with that a little longer than we're used to?

Willow

Well, speaking of the created creating the creator, I'm going to bring this conversation full circle back to you learning from your son. Our final question for anyone who's listening to this who is perhaps sitting there staring at the puzzle pieces of their life at this moment, if there's one piece of wisdom that you had for them, what would it be?

Bayo

The puzzle isn't yours. It's not yours. We have labored under the impression that we have to put things together, that we are the owners of ourselves, that we are the owners of our own lives. My son taught me that I don't have to adhere to the prescriptions of the manufacturer. I don't have to. And in so doing, he offered wisdom that the puzzle isn't yours. The puzzle is a playground that is already infiltrated by the things that we have longed to keep outside of modern civility. Our lives are already the playgrounds of microbes and monsters, of ancestrality, of algorithms and software, and hardware and futures and stranger temporalities that Dan could fit on a linear timescale. And so, maybe this is the time for listening to the others. Maybe selves, our soulscapes. Maybe we have reduced the soul to the disembodied ghost that lives within our flesh. Maybe like the etymology of the word "soul" suggests, the soul is the "sea" and the sea is always populated by the others. Maybe our souls are strange, and we haven't met them yet. Maybe the puzzle isn't ours.

Willow

And maybe the puzzle is the playground.

Bayo

Yes.

Willow

Beautiful. I can't think of a more perfect place to end. Thank you so much, Bayo. I always receive so much from our conversations, and I can already feel the grooves in my mind forming.

Bayo

Thank you, Sister. As always, we do great together. Thank you.

NARRATION

At the end of each episode, I offer prompts for guided self-reflection to help internalize and investigate how this week's themes show up in our daily lives and how we can apply the principles discussed. For this week, I wanted to share a practice in my life that's related to what Bayo shared around the third way. Whenever we're faced with a decision, I've noticed that our minds tend to gravitate toward only two options. We tend to jump straight into "this" or "that" thinking. So, instead, I'll invite you to ask yourself, "What's the third option?"

In my life, I often find that the third option looks like something balanced between the two, or one that throws out the instructions altogether. So, when you find yourself in a position of making a decision, ask yourself, "What's the third option?"

The Nature Of is an Atmos Podcast produced by Jesse Baker and Eric Nuzum of Magnificent Noise. Our production staff includes Julian Natt, Eleanor Kagan, and Daniel Hartman. Our sound designer is Kristin Mueller. The executive producers of The Nature Of are me-Willow Defebaugh-Theresa Perez, Jake Sargent, and Eric Nuzum.

Atmos is a nonprofit media organization focused on the cross-pollination of climate and culture. In addition to our podcast, we deliver award-winning journalism and creative storytelling through our biannual print magazine, daily digital features, original newsletters, and more. To support our work, see our show notes or visit our website/biome at that's A-T-M-O-S dot earth, slash B-I-O-M-E. I'm your host Willow Defebaugh, and this is The Nature Of.

- Activists often find themselves entangled with the problems they seek to solve, as the ways they respond to crises can sometimes be part of the crisis itself.

- Bayo Akomolafe, the guest on the podcast episode, promotes the concept of post-activism, encouraging people to question whether their actions might unwittingly maintain or exacerbate the issues at hand.

- Embracing the third way, or the space between and beyond binaries, can help us navigate the complexity of contemporary issues and find new ways of relating, knowing, and becoming.

- Nature doesn't necessarily solve tension; instead, it composts it, making way for unexpected possibilities to emerge.

- The Emergence Network, founded by Bayo Akomolafe, seeks to bring together communities in response to the challenges faced by humanity as a species.

- In a world full of urgency and compounding crises, slowing down and allowing ourselves to be present to what is emerging can open up new possibilities for regeneration and renewal.

- The natural world, with its processes of emergence, offers insights into how to navigate the experience of being human.

- Education-and-self-development and personal growth are integral aspects of navigating the complexities of contemporary culture and relationships.